Scroll↓

In regard to the slightly dramatic title of this essay, the origins of the topic came about by the desire to explore the influence of art in the downfall of empires. However, as I began exploring this topic, the research revealed the origins of how we came to think about art today. The focus then began to shift towards investigating what art is. This was because these origins made me deeply question my previous definition of art and its legitimacy. The following essay is an exploration of what art is by examining who it works for. From despotic Italian Lords to the CIA. This essay will explore the power of art and the importance of critical evaluation. The aim of this essay is to teach the reader, and through research, inform myself of the history of art, in regard to who it works for, as this is a key component in discovering what its role is. The power of art is undeniable and has been used throughout history in both positive and negative ways. Using historical and political lenses, the essay will evaluate the intentions of art, its makers, and its funders in order to understand what it is. First it will explore the beginning of the artist, and the first school of art set up in 16th century Florence. It will identify how a hierarchy of the arts was set up and its effects. It will use case studies to demonstrate these theories. It will then explore the changes that art took, between the Renaissance and the 19th century, and the seminal figures and events that forced the change. Then, to prove the necessity of critical evaluation of art, it will analyse how the history of art has been hidden, providing examples of the covert manipulation of art distribution from WWII to modern day. Finally, it will talk about how art, and political art movements are being co-opted and mystified, using commercialisation, and the importance of constant critical evaluation.

Before the Renaissance began in the 14th century, the word artist was not commonly used. More common was craftsman, or in some cases artisan (Witham). These craftsmen worked in the guilds, “an association of craftsmen or merchants formed for mutual aid and protection and for the furtherance of their professional interests.” (Britannica). Crafts such as weaving, metalsmithing, and painting all belonged to their separate guilds. “Guilds performed a variety of important functions in the local economy. They established a monopoly of trade in their locality or within a particular branch of industry or commerce… and they sought to control town or city governments in order to further the interests of the guild members and achieve their economic objectives.” (Britannica). The craftsmen themselves had very little control over the purpose of what they were making. They existed as skilled labour but nothing more. During the late 14th and early 15th centuries certain people began to evolve how craftsmen were seen. A new type of artisan emerged. The artist. The artist diverged from the craftsman because they took control of their own output. Giorgio Vasari “one of the foremost artists of 16th century Italy” (Wood) argued “that the best artists had "divine inspiration”” (Witham). What he meant by this is that art needed to have a deeper moral cause or meaning. Despite these proclamations, the wider world was not yet convinced about artists, and so began the journey to legitimise art. Early attempts to start art schools and academies began in the 16th century across Italy. “The rise of the academies was part of a general attempt by artists to modify their social status” (Langmuir 1986) and distinguish themselves from craftsmen. But the first true art school, The Accademia del Disegno, was set up in 1563 by two influential figures in art history. Giorgio Vasari, widely known as the father of art history, and Grand Duke Cosimo I de ‘Medici (Jack 1976: 7). Cosimo, part of the Medici family, became the Duke of Florence in 1537. Despite his age at the time, 17, he did not hesitate to consolidate his power, and following his defeat of an invading force of exiles and neighbours, he promptly beheaded all the prisoners. This is to say, he was a classic despotic ruler (Britannica). Hard influence, however, was not his chosen tool of power, as Cosimo became one of the most influential patrons of the arts in history. Together, with his wife, Elenora di Toledo, he set about reforming Florence into a place of massive cultural influence, which still to this day, remains the epicentre of the most recognisable art period in history. The Renaissance. “[Duke Cosimo] wished to harness art to legitimize and publicise his own standing and his dynastic aspirations. To this end he set about controlling not only the production of art but also the training of artists.” (Langmuir 1986). Needless to say, Duke Cosimo had much to gain by controlling the narrative of art. However, to do this art needed to be legitimised, the social standing of artists needed to be raised to that of poets and philosophers. And crafts needed to be separated from the influence of the guilds. So, Duke Cosimo and Vasari started the first art school. The Accademia del Disegno “was the most important institution for Florentine artists in the late sixteenth century.” (Jack 1976: 1) and therefore, during the Renaissance. They created a hierarchy of art. Landscape and genre (scenes of everyday people and things) were regarded as lower value, portraiture of medium value, with the larger the painting the more valuable, full body being the gold standard; And finally, taking the top spot, narrative, story, or history paintings (Langmuir 1986). Naturally the artworks that could carry the most meaning were regarded as the most significant. The role of the artworks created by The Accademia del Disegno were not really so different from the guilds, but they appeared so. This is why the importance of The Accademia del Disegno cannot be understated. It simultaneously legitimised artists and created a hierarchy of the arts in which political power and acts could be justified.

Art was legitimised by the art schools. The ideas first tested by The Accademia del Disegno were carried on by many different influential art schools. The Accademia di San Luca, The Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Langmuir 1986), and they are carried on today. John Berger argues that to critically evaluate art you must understand the entire context in which it was created. He says when something is seen as art it carries with it preconceptions such as beauty, or the genius of the artist. This means that art can be easily misinterpreted, and its true meaning forgotten or hidden (1972). He argues that the whole history of how we see art has been warped by these preconceptions of art and “Certain exceptional artists in exceptional circumstances broke free of the norms of the traditions and produced work that was diametrically opposed to its values” (1972). One in a million artists that we know of were creating art that opposed hierarchical values, but their works of art define entire periods of art. These artists “had no followers but only superficial imitators.” (1972). And so, the true meaning of the majority of art is hidden from most people studying that art. To analyse art, you must consider its context. Doing so makes it abundantly clear what the motives of its creators are. Here are two pieces of art created for Duke Cosimo. The first, a portrait (Fig 1), and the second, a marble relief (Fig 2). These two pieces sit at the top of the art hierarchy. A large portrait and a narrative piece done in the style of a historical artwork. In figure 1, “Is Cosimo meant to be seen as a peaceful Mars, god of war, his helmet removed, ready to govern? Or is he likened to his father, who had been a famous soldier?” reads the description by the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET). It is clear that the painting was created to make Cosimo seem powerful and wealthy. See the deep, rich materials of the velvet curtain and the full suit of armour. But notice the pose too. Berger argues that oil painting has the ability to create such life like objects, full of texture, which create a closeness to the subject. So, when artists are painting the wealthy elite “They are there in all their particularities and we can study them, but it is impossible to imagine them considering us in a similar way.” (1972). This is why Duke Cosimo is looking away from the viewer. Often in paintings of the elite, there is an awkwardness manufactured to create distance between the viewer and the subject. Early Renaissance art portrayed figures of power, more often than normal people, to place them on a pedestal to be admired, but not understood. In this way we can admire their moral values, but not understand them, and therefore not question their decisions. Figure 2 is an “allegorical marble relief” depicting “Cosimo’s many initiatives in Pisa” (MET). It is a narrative portrait and in the style of Roman art, which often depicts mythological stories. Berger argues that the role of the classics “was not to transport their spectator-owners into new experience, but to embellish such experience as they already possessed.” (1972). Duke Cosimo has gone a step further than the traditional classic, and had himself in place of the heroes of myths. Classical styles and narrative art inspired by mythology lends an authority to whoever is depicted, regardless of their actual actions. These two pieces do well to sum up the art of the period. However, they do not come close to defining it. To hold these pieces of art in high regard, under the guise that they are pieces deserving the praise of genius, reveals how art it used by the powerful. It is used to justify power.

Between the 15th and 19th centuries, art remained fairly consistent. There were many art movements such as Mannerism, Baroque, Dutch, Rococo, Neoclassical, Romanticism, and Realism. But despite this, the different movements didn’t make drastic changes. This is not to say that great art was not created during this time, but often the movements acted in a cyclical nature between decadent detail and strict realism. The hierarchy remained much the same during this time although landscapes were prominent during the Romanticism movement. But after this long period of relative stagnations in art, the beginnings of change were emerging. “In 1789 the simmering free-thinking of Montaigne, Montesquieu and the Encyclopaedists burst like a bomb.” (Ozenfant 1952: 2). “The right to think was delivered from all legal interference and from all penalties whatsoever.” (1952: 2). Ozenfant puts forth that during the French Revolution free thinking emerged from captivity. And Philosophers, mathematicians, scientists, and poets led a radical change in the way we think. He argues that the landscape painters of the romanticism period were the first to break the mould, but they are forgotten of this role as the “instinctive” revolutionaries by the “professional” revolutionaries that came after them. The Impressionists (1952: 4). Early in the 19th century came the most profound change in the art world since the Renaissance. The invention of the camera. John Berger, in his essays the ways of seeing, explains how this invention fundamentally changes how we made art. He argues “An image is a sight which has been recreated or reproduced.” (1972). This frames his argument with the artist as an integral part of the art. He says “Before the camera, perspective centres on the eye of the beholder. Appearances travel inwards, towards the viewer. This was reality, the one and only reality. The art was always from the perspective of one person. Often you can see the subjects of the art interacting with the person painting them, or the narrative intended viewer. Cameras changed this. They decentralised perspective and presented the idea of different realities from the same event.” (1972). This new way of seeing changed how people though. Art was very often used for justification, be that of wealth, power, or glorifying events. This new way of seeing enabled people to see who art was beholden to, and to act upon that. The viewer became aware of their presence in the art, and the presence of others. This was the start of modern art. This explained the sudden and drastic change you see in art in the 19th century, from the New Raphaelites to the Impressionists. “For impressionists the visible no longer presented itself to man in order to be seen. On the contrary, the visible, in continual flux, became fugitive.” (1972).

There are many artists you could argue are the most important to the modern art period. Pablo Picasso or Henri Matisse. But more than any other, Marcel Duchamp, recontextualised how we think about art today. His work was pivotal in understanding, and the partial undoing of what Duke Cosimo and Vasari had created centuries before. Judovitz describes Marcel Duchamp’s career as “That of the abandonment of painting followed by the renunciation of conventional art forms.” (1998). He had been a painter during the early 20th century but abandoned it by 1918 and “by 1923, he has ceased to produce conventional art altogether” (1998). Duchamp moved away from the mimetic nature of art, its beauty, and focused on its meanings. “While other modernist movements such as Cubism and Fauvism turn to abstraction as a way of responding to the social and technological changes, Duchamp turns to a conceptual investigation of the meaning and function of art.” (Judovitz 1998). His most influential works include, Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 1), the ready-mades, and Box in a Valise (Fig 4). The most well known of these works is the Fountain, (Fig 3) one of the ready mades. The ready-mades were, as stated, ready-made items like a shovel, a fountain, and a window. They were all mass-produced objects displayed as art. The meaning of the piece was “It suggests that artistic production is a system that reproduces and reassembles the conventions that frame and label various works as art objects.” (Judovitz 1998). When you look at the foundations of what art was at that time, as created by Duke Cosimo and Vasari, these pieces of art, directly oppose the system. Duchamp was arguing that no piece of art was original, that all art was created in a system, and followed rules. The point of the artworks was to demonstrate how artists were working. His work does not aim to degrade artists, he aims for the opposite. To make art using a system created by the powerful is to be complicit in its motives. Only when you critically evaluate what you are making, its rules and meanings, can you be truly creative. Another of his works is Box in a Valise (Fig 4). This piece is as he put it “Everything important that I have done can be put into a little suitcase.” (Judovitz 1998). He created twenty-four cases, and each had over sixty miniature replicas of his work. This piece continues to explore originality in art. Being one of twenty-four pieces would make it a replica in the eyes of the art world. However, Duchamp made no distinction between which was the original. In fact, Duchamp was exploring “the notion of reproduction and the multiple as a way of redefining art” (Judovitz 1998). “Duchamp redefines the artist as a maker, rather than a creator. This is not because Duchamp denies the powers of either inspiration or creativity but because he recognizes that any creative act is embedded in expectations that predetermine its outcomes.” (Judovitz 1998). This opposes the ideas of The Accademia del Disegno, as its whole existence was to justify artists and make the distinction between artists and craftsmen. Or creators and makers as Judovitz puts it. When Duchamp redefined the artist as a maker, he stripped away the pretencious nature of what is called high art, and argued the creative act as something that does not follow rules set out centuries before, but something that can act as a instigator to deeper thought. Briefly stepping back in time, in 1768, the first art school in Britain was set up with permission from the king, George III. The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) was set up with the same founding ideas as the Académie de Peinture et de Sculpture. In turn the founding ideas from the Académie de Peinture et de Sculpture came from the Accademia di San Luca which in turn came from the Accademia del Disegno and Duke Cosimo and Vasari. Joshua Reynolds, one of the key founding members of the RA, created a set of fifteen discourses on which the principles of the school were to be built. “According to Reynolds, the ‘great style’ endowed a work with ‘intellectual dignity’ that ‘ennobles the painter's art” (Royal Academy 1769-1790), very similar views to Vasari. In post war Britain, the Modernism movement was beginning to fade. Society was “Shorn of the confidence about projecting the art of the future” (Brazil 2016). In 1946 the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) was established by six men who were tired of the confines and traditions of the Royal Academy. The ICA began the revival of Modernism, into what is known as Late Modernism. “The most important consequences of its reconstruction of modernism in postwar Britain were felt by artists, architects, theorists, and also – though not immediately – writers.”. Clement Greenburg and Theodor Adorno argued that Modernism could “only be sustained through an isolated investigation of the formal laws of each respective artistic medium.” limiting Modernism to the traditional art world. However, the ICA refocused the efforts of the movement to become “an interdisciplinary phenomenon”. “The ICA attempted to diverge from this understanding of modernity, as institutional and disciplinary, precisely in order to remain open to the “unknown art of the future.”” (Brazil 2016). Both Marcel Duchamp and the ICA pushed conceptual art to the limits. Art could not be held back by the confines of aesthetic function, nor could aesthetic function be relied upon entirely to call something art. Meaning was yet again the most important part of art, but it had shifted away from protecting the wealthy, to critiquing and revealing its intentions.

If the works of Duchamp and the rise of modern art, free thinking, the ICA, and the camera succeeded in breaking the hierarchy of art, and bringing into question its motives, these effects did not last long. It has never been a question of breaking free from the control of the powerful once and for all, it must be a concerted and constant effort. History proves this as time and time again art has been under the control of the wealthy. Despite this, artists have never ceased to produce work that pushes boundaries and breaks the rules. This is why it is essential to critically evaluate your own work, and who it is for, constantly. So, what of modern art? “Modernism in fact, became a weapon of the cold war. Both the State Department and the CIA supported exhibitions of American art all over the world.” (Levine 2020). In an effort to separate themselves from the Soviets, the American government turned to art to project an idea that America was a free country. Eisenhower, somewhat ironically, said “As long as our artists are free to create with sincerity and conviction, there will be healthy controversy and progress in art. How different it is in tyranny. When artists are made the slaves and tools of the state; When artists become the chief propagandists of a cause, progress is arrested and creation and genius are destroyed.” (Levine 2020 [Eisenhower]). “The relationship between modern art and American diplomacy began during WWII, when the Museum of Modern Art was mobilized for the war effort.” (Levine 2020). MoMA took on an important part in creating a sort of propaganda of art. The CIA and the American government did not create Modern art, but they did successfully realise its power, and harnessed it. “MoMA fulfilled 38 government contracts for the cultural materials during the Second World War” (Levine 2020) and two former presidents of MoMA, John Hay Whitney and Thomas W. Braden, became some of the founding members of the CIA. “the CIA fostered and promoted American Abstract Expressionism painting around the world for more than 20 years.” (Saunders 1995) and influenced the work of prominent artists such as Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, Witten de Kooning, and Mark Rothko (Saunders 1995) The influence of the CIA did not end in America. “In 1950, the Agency created the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF)” (Levine 2020). This new agency, set up in Paris, masqueraded as an independent group set up by artists. “the CCF’s main goal was to convince European intellectuals, who might otherwise be swayed by Soviet propaganda” (Levine 2020). The role of the CCF was to publish magazines, hold conferences and exhibitions, and give rewards. The CCF ran for seventeen years “at its peak, “had offices in thirty-five countries” (Levine 2020). It funded the Partisan Review, a left-wing magazine which had association with T.S. Elliot and George Orwell. The CIA is just one example of Governments becoming involved in the world of art for their own benefit. They took a leaf out of the book of Duke Cosimo, who started it all. However, it is not always the covert promotion of art by governments that is the most dangerous; because the promotion of art by the institutions we expect, comes with much less scrutiny.

In 1971, Hans Haacke’s solo show at the Guggenheim was cancelled. The contents of the show were indicative of the themes, of illuminating systems, that he pursued throughout his career. The show consisted of photos of the buildings of several powerful businesses and real estate holdings, and next to them, the photos of slums. There was also a questionnaire for visitors to fill out. “At this point Haacke forces each viewer to make an unconscious decision based on class sympathies and affiliations. Either a viewer mentally sides with the occupants of the slums … or with the owners of the slums” (Burnham 1971), depending on what answers they give to the questionnaire. “However a spectator decides, Haacke discloses a crucial relationship; this is the indirect and invisible way in which financial holdings define environmental esthetics. At a gut level Haacke is asking the question: is there really any difference between the power of money to control the direction of art and the power of money to keep rotten slums in existence?” (Burnham 1971). In short, that the museums and galleries that display art to the public, work on the same systems that the corrupt and cruel systems of business do. Steinberg says on the exhibit “The owner of these prolix properties – 142 buildings, including a generous portfolio of slums – was evidently a man of substance, probably a philanthropist, a donor perhaps to this very museum.” (1986). This is in fact what Haacke went on to do with the rest of his career. Uncover the shady financial backers or art museums and galleries, and then display that information within them. Hans Haacke’s work raises the question, “to what extent can art exist outside of history and politics?” (Steinberg 1986). When the Guggenheim cancelled his exhibition, in the words of Howard Wise, “you now become part of the work of art.”. Haacke had achieved “the complete integration of his art, leaving no essential dividing line between his professional life and his existence as a social and political creature.” (Burnham 1971). His work defies the typical interpretation of art, about beauty, and instead lays out facts. It is presented in a way to transmit a message rather than to be pleasing to the eye. This is not a form of rebellion; it is simply the best way to get the message across. “In a climate of growing artistic compliance, with abundant pleasers adorning the lobbies and boardrooms of corporations, Haacke’s [work] … [ventures] into a factual reality so specific, so unappealing and potentially libelous that one is forced to either refuse it the status of art or, once again, to rethink definitions and erase previous limits.” (Steinberg 1986).

Art through history has often been the mouthpiece of the wealthy and powerful. It has been used as a tool for the justification of wealth and power. Artists like Duchamp, Haacke and many others are in a minority of those that evaluate the state of art, and their own work, to avoid supporting its underlying intentions. But why is it the case that the majority are complicit or at least unaware of what they are contributing too? John Berger argues this is due to the mystification of art. Berger argues art is mystified by multiple different methods. He argues first that “When we are prevented from seeing it, we are being deprived of the history which belongs to us… In the end, art is being mystified because a privileged minority is striving to invent a history which can retrospectively justify the value of the ruling classes.” (1972). Art being hidden in collections of the wealthy is a prime example. However, this does not explain art in current times, as most art is available for all to view online. Therefore, more layers of mystification have been built to control the understanding of art. Berger argues that by explaining art in structure and form mystify the true meaning of art. Art critics, especially in education can play a large negative role of alienating people with complicated jargon. For example, do the mystery of Mona Lisa’s eyebrows contribute anything towards the actual meaning of the artwork (Fig 5)? He also argues that the commodification of art is used to the same end, and that art also had a role in creating the system of commercialisation today. “Oil painting did to appearances what capital did to social relationships. It reduced everything to the equality of objects. Everything became exchangeable because everything became a commodity.” (Berger 1972). Berger argues that value of art has had a tremendous effect on the way we view it. He says value has become a “bogus religiosity” (1972). Who can put a value on creativity? This has changed the way in which we view art because when an extreme price is put on a work of art it entirely eclipses what the art actually means. When visiting a museum, you do not tend to think what the most famous artwork on the wall means, your absorbed with thinking, this is the real thing! The massive values of art are also used in more practical ways to maintain wealth, such as tax avoidance. The artist Peter Doig famously said, “My work sells for millions but only a fraction of that came to me” (Doig 2024). In a conversation about the commodification of art, especially music, Anthony Fantano and F.D. Signifier use the example of a tweet by Tom Morello of the band, Rage Against the Machine. He tweeted, “Never ceases to amaze me how many folks who’ve heard RATM are in Paul Ryan mode, having literally ZERO understanding of anything that band was about and even less understanding where any of us might stand on contemporary issues.” (Morello 2024). Fantano and Signifier frame their conversation around the question, “Why is it that we’re currently existing in an age where there are so many people who very loudly and aggressively just don’t really seem to get or understand what the political ethos is behind bands like Rage Against the Machine?” (2024). They argue that even the art that is created with positive motives can be used in negative ways through the co-option of art. They argue that the rise of social media and the decline of in person interactions have a lot to answer for in regard to the acceleration of the commodification of art, by right leaning political factions. They theorise that “a lot of this [art] has been rendered essentially meaningless … we are kind of enjoying and embracing all of these styles … just for aesthetic sake” (Fantano, Signifier 2024). They argue that the commodification of music is to answer for the dilution of political messages. “The internet allows you to … casually embrace it without actually having to do the work to understand the deeper meaning and the history” (Fantano, Signifier 2024). Social media platforms and internet browsers mystify the meanings of political art movements such as punk music. These movements, now practically devoid of their original meanings, are then co-opted by the Right. Fantano jokes, “Conservatism is the new punk rock.”, explaining that there is a mistaken idea that counterculture is currently about being anti-liberal. This manifests itself in aggression towards minorities, which opposed to counterculture is often encouraged by media and governments to create scapegoats. The co-option of art is much more likely to happen if the meaning of the art is not overtly explained. They say that modern music audiences often self-police this using social media platforms, however less mainstream and older genres of music are co-opted more easily from a lack of vigilance. Finally, they say that the left needs to continue to make new art, as they always have, in order to slow co-option, and gain influence (Fantano, Signifier 2024).

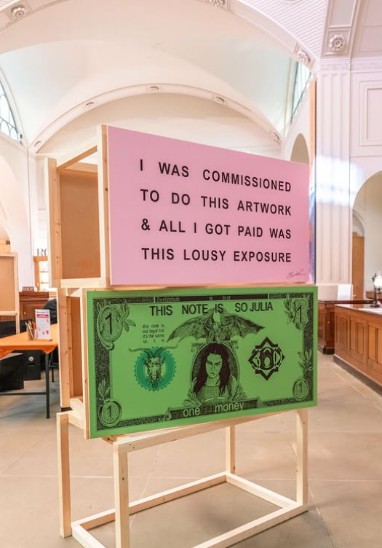

Whilst evaluating Hans Haacke’s work, Steinberg and Burnham both refer to artists as a jester, or “like fools in motley at the courts” (1986) (1971). Their meaning by this description is that artists are supposed to entertain their lords, so to speak. This makes a good analogy for how we should treat making art. There are two ways of defying the system that art is made in. Firstly, by leaving it. Leaving the system does not mean to abandon art, but to stop making art for the people that maintain the system of art and hierarchy. As a graphic designer, in my practice this would entail working for educational, artistic, and charitable purposes. This method still requires in depth analysis of the party that you are working for, as any one of these may be complicit in systems of control. This method of working is beneficial, but only to a certain extent. If every artist would, or could, work in this way then art could be freed of its bonds. However, everybody working in this way is impossible, both ideologically and financially. The second way of defying the system has the potential to have greater effect than the first one mentioned. Instead of leaving the system that creates art, remain in the system, but defy its laws. One of Bruce Mau’s beliefs from his Incomplete Manifesto for Growth states, “Design what you do”. This belief is demonstrated during a business conference he did for Coke after working with them to “redesign its business to be more sustainable”. A question was posed from the audience, “Why not just stop making Coke?” due to its damage to the planet. Mau replied, “I hear what you’re saying, … but I don’t think ‘no’ is the answer to these challenges. Denial – just telling people you can’t do this or that – will not get us to where we want to be. We have to redesign the things we love so we can keep enjoying them.” (Berger 2009). This outlook when creating art can have a profound impact on art and society as a whole. To deny working with organisations that maintain systems of control, is to deny yourself the opportunity to change the systems of control. The artists that this essay has explored have all worked within the systems of control, to a certain extent. They have broken the rules, and therefore their work has become meaningful because it has discovered and explored news way to see art. To give an example, a recent project by the artist Harriet Richardson for the Bank of England clearly illustrates how to work within a system of control but break the rules. Richardson was approached by the design agency Kesselskramer who were curating an exhibition on behalf of the Bank of England on “the theme of ‘the future of currency’” which Richardson said, “was too much of an opportunity to pass up.” (2024). Despite the exhibition being on currency and being held by a bank, it was not a paid project. In an interview with Kesselskramer for the job, the representative of Kesselskramer said “we had a couple of responses that were quite angry … which surprised me.”. He said the payment was in exposure which he called “very unquantifiable”. Richardson pointed out that “there’s some people that benefit and then there’s some people that facilitate.” With the interviewer responding, “I’m not benefiting mate” (Richardson 2024). Richardson created the top piece of work in figure 6. A typographic piece with the enlarged dimensions of a bank note (the standard size for the exhibition) which read ‘I was commissioned to do this artwork & all I got paid was this lousy exposure’. The piece of work, along the with interviews and emails was posted to her Instagram with the description, “I hope this piece ‘Exposure’ is received as the conversation starter it’s intended to be. Although I don’t wish to single out any one design agency or creative, I can’t stress enough the importance of calling out bad practice whenever possible.” (Richardson 2024).

This essay has briefly explored what art is by looking at its history. The research began with the history of the first art school, which was set up to legitimize artists, to create a new form of power. Looking at art in this way would suggest that its intentions are mainly negative. However, during the next few centuries, many artists created truly positive works of art. Although, these were used to lift the presumed quality of other, more insipid works. During the 19th century, the invention of the camera, and the revolution of free thinking changed the way the human race though, and birthed a new type of art, Modernism. Art was no longer contained by the strict visual hierarchy created by the first school of art, but it certainly was not free from control. Artists like Duchamp and Haacke were key to revealing the true nature of art. The essay then explored how the mystification and co-option of art has plagued understanding and meaning. This explains the necessity to constantly critically evaluate art and its intentions, and to constantly work to out create the systems of control that justify power. So, what is art? Art, just like any other word, is just a word. People give meaning to the word art and often question whether something is art or not. Think of Duchamp’s ready-mades, not a traditional form of art, but most people look back on them as art and hold them in high regard. People also hold the Mona Lisa in high regard when it could not be further from the ready-mades. A distinction is often made that graphic design is not art because it is made for a client, but as this essay has shown, often that is the case for traditional arts too. Art is something held in a museum or in the collections of the rich. Art is also the fingerpainting of a young child. Art means different things to different people and seems to be in constant contradiction to its own meaning. Governments see art as a tool of promotion and control, others see art as a form of rebellion, and others again see art as a form of entertainment. If this essay can prove one thing, it is that we should not try to force art to be one single thing. That would only be giving in to the hierarchy created all the way back during the renaissance. It is also a futile effort, trying to define art, because it changes so often. Art has meant so many different things through history and will mean many different things in the future. How will AI change how we view art? Will there be a revolution in thinking as when the camera was invented? Or will we return to tradition? Art does not have a single meaning. This does not mean we should create art without meaning. Because art does have the power to change the way people think. It has the power to illuminate systems of control and to discover entirely new perspectives. Be critical of what you see because art has power, and be critical of what you make because art has power. Art can end empires, but it can just as easily start them too.

Figure 1: Bronzino. 1554. Cosimo I de' Medici in Armor. The Metropolitan Museum of Art [online]. Available at: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/821862?exhibitionId=%7B2c98eb4f-1cd0-43dc-912e-1fd5d5ef9c00%7D&oid=821862&pkgids=689&pg=0&rpp=100000&pos=12&ft=*&offset=100000&locale=en [accessed 03 Dec. 24 2024].

Figure 2: Pierino da Vinci. 1550-52. Cosimo I de’ Medici as Patron of Pisa. The Metropolitan Museum of Art [online]. Available at: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/821923?exhibitionId=%7B2c98eb4f-1cd0-43dc-912e-1fd5d5ef9c00%7D&oid=821923&pkgids=689&pg=0&rpp=100000&pos=17&ft=*&offset=100000&locale=en [accessed 03 Dec. 24 2024].

Figure 3: Marcel Duchamp 1917. Fountain. Wikipedia Available at: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fountain_(Duchamp) [accessed 04 Dec 2024]

Figure 4: Marcel Duchamp Marcel Duchamp 1935-41. Box in a Valise. MoMa [online] Available at: www.moma.org/collection/works/80890 [accessed 04 Dec 2024]

Figure 5: Unknown 2014. Imgur. Available at: imgur.com/QQLmT2A [accessed 04 Dec 2024]

Figure 6: RICHARDSON, Harriet. 2024. Exposure [Instagram]. Available at: www.instagram.com/p/DAGttG9xUkc/?img_index=1 [accessed 13 December 2024].

BERGER, John. 1972. Ways of seeing. Available at: www.ways-of-seeing.com/ [accessed 19 November 2024].

BERGER, Warren. 2009. Meet Bruce Mau. He wants to redesign the world. Wired. Available at: brucemaustudio.com/press/meet-bruce-mau-he-wants-to-redesign-the-world/ [accessed 10 December 2024].

BRAZIL, Kevin. 2016. Histories of the Future: The Institute of Contemporary Arts and the Reconstruction of Modernism in Post-war Britain. Johns Hopkins University Press. Available at: muse.jhu.edu/article/609698 [accessed 12 December 2024]

BRITANNICA. n.d. guild. Britannica Available at: www.britannica.com/topic/guild-trade-association [accessed 05 December 2024].

BRITANNICA. n.d. Cosimo I. Britannica Available at: www.britannica.com/biography/Cosimo-I [accessed 20 November 2024].

BURNHAM, Jack. 1971. HANS HAACKE’S CANCELLED SHOW AT THE GUGGENHEIM. Artforum. Available at: www.artforum.com/features/hans-haackes-cancelled-show-at-the-guggenheim-213684/ [accessed 10 December 2024].

DOIG, Peter. 2024. ‘My work sells for millions but only a fraction of that came to me,’ says Scottish painter. Guardian. Available at: www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/article/2024/aug/31/peter-doig-scottish-painter-secondary-market-prices [Accessed on: 15 December 2024].

FANTANO, Anthony. SIGNIFIER, F.D. 2024. When You Completely Miss the Point [video].

Available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=B5p2-iN7XeA [accessed on: 14 December 2024].

JACK, Mary. 1976. The Accademia del Disegno in Late Renaissance Florence. The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 7. Available at: www.jstor.org/stable/2539556?saml_data=eyJzYW1sVG9rZW4iOiJhNWM0NWM1YS01ZTkzLTRlM2UtYjhmY

i03ZTQ1ZDdmYWZlMjIiLCJpbnN0aXR1dGlvbklkcyI6WyI1ZjQyMzY1YS1hMTEyLTQ0ZjEtOTk0My0wMmVhNGRmYjFjMDkiXX0&seq=5 [accessed 21 November 2024].

JUDOVITZ, Dalia. 1998. Unpacking Duchamp: Art in transit. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, and London, England. University of California Press

LANGMUIR, Erika. 1986. Introduction to art history. Open University. Arts Foundation Course Team. Open University.

LEVINE, Lucie. 2020. Was Modern Art Really a CIA Psy-Op?. JSTOR. Available at: daily.jstor.org/was-modern-art-really-a-cia-psy-op/ [accessed 05 December 2024].

MET, The Metropolitan Museum of Art [online]. Available at: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/821862?exhibitionId=%7B2c98eb4f-1cd0-43dc-912e-1fd5d5ef9c00%7D&oid=821862&pkgids=689&pg=0&rpp=100000&pos=12&ft=*&offset=100000&locale=en [accessed 03 Dec. 24 2024].

MORELLO, Tom. 2024. Paul Ryan mode [Twitter]. Available at: x.com/tmorello/status/1853187381282615702 [accessed 13 December 2024].

OZENFANT, Amédée. Translated by John RODKER. Foundations of modern art. Dover Edition. New York. Dover Publications, inc.

RICHARDSON, Harriet. 2024. Exposure [Instagram]. Available at: www.instagram.com/p/DAGttG9xUkc/?img_index=1 [accessed 13 December 2024].

ROYAL ACAMENY. 1769-1790. Papers relating to Reynolds's discourses. Royal Academy. Available at: www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/archive/papers-relating-to-reynoldss-discourses [accessed 10 December 2024].

S

AUNDERS, Frances. 1995. Modern art was CIA 'weapon'. Independent. Available at: www.independent.co.uk/news/world/modern-art-was-cia-weapon-1578808.html [accessed 05 December 2024].

STEINBERG, Leo. 1986. Hans Hacke: Unfinished Business. New York. The New Museum of Contemporary Art

WITHAM, Larry. n.d. When Did the ‘Craftsman’ Become an ‘Artist’ in Western Culture?. Available at: www.withamartstudio.com/painturian-blog/when-did-the-craftsman-become-an-artist-in-western-culture-painturian-no-47#:~:text=It%20could%20be%20said%20that,calling%20such%20adepts%20%22artisans.%22 [accessed 27 November 2024].

WOOD, Kelli. n.d. National Gallery of Art [online] Available at: www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.3269.html [accessed 20 November 2024].